April is indeed the cruelest month... Part 1

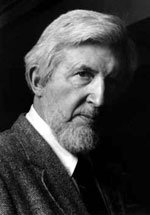

“April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.”

- T.S. Eliot

The Burial of the Dead,

from The Waste Land

April has nearly passed; and I, for one, wish it good riddance.

April, for the uninitiated, is National Poetry Month; a month where the proselytisers of verse, or things approximating verse, gain the fleeting attention of the manic news cycle if only for an instant. Magazines, newspapers, and other periodicals along with television, radio, and other forms of electronic media make a little space for the art form we call poetry. Readings spring from the ground like Morrell mushrooms in the rain. Snippets of verse are splashed upon posters in subways and buses; banners on street corners proclaim that poetry is good for you. I know “Guinness is good for you” (their marketing is more convincing), but poetry?

This would be all be well and good, if it were not so damned patronizing. Poets are paraded out, interviewed, and flattered for thirty glorious days every spring. Well, at least since 1996 anyway, when the Academy of American Poets created NPM. Withering like blooming dogwoods and daffodils; at the stroke of midnight on the eve of May Day, the poets are expected to return to their lairs and garrets for another 335 days of consulting their muses or, more probably, teaching creative writing courses. Patted on the head and sent on their way with a dismissive “Same time next year?”

Every year editorials in small literary journals figuratively wring their hands and ask the question: Is there an audience for poetry? To paraphrase Bill Clinton, it depends on what you mean by audience?

With the massive expansion of creative writing programs both on the undergraduate and graduate level, the United States is producing poets far in excess of its readers. While the teaching posts and literary magazines have increased exponentially, the numbers of general readers of poetry (along with all literary forms) has plummeted precipitously. There are a myriad of reasons this has occurred – modern forms of entertainment such as movies, television, etc., but there are some who blame the poets themselves.

In the 2500 years between Homer and Ezra Pound there is an unbroken tradition that only started breaking down in the twentieth century. A hundred years ago the term “free verse” was unknown to those studying prosody. “The long revolt against inherited forms,” Billy Collins, the former Poet Laureate of the US, said, “has become the narrative of 20th poetry in English”

Every morning I find missives, or rather e-missives, in my mailbox from various literary ‘zines reminding me to peruse their latest poetic offerings on the World Wide Web. Poetry Daily, one of the better sites, features a poet every day from what is considered the best contemporary poetry has to offer. After avidly reading the site for several months, the frequency of my visits declined because I found less and less to bring me back. Still, hope springs eternal and I clicked on the link to find this poem by Stephanie Marlis some time ago that had been published in the Chicago Review:

Transsexual Cloud

all through this metamorphosis we hunt for therapies.....burly reasons

ours, a knot that does not slip............ thunderclap

yellow basin..... settles behind a cloud......... lemon blouse...... carries the trash

only curly leaves befuddle me and you........ were a chiseled man

so long

My first thought upon reading these two “poems” was how wonderful it is that the Chicago Review should publish the works of recovering stroke victims. The lack of grammar, scansion, the non sequiturs, the erratic spacing and the utter lack of sense would lead the reader to believe he was reading the work of someone who had suffered severe damage to the part of the brain controlling language.

I made several attempts to unravel the puzzle, including reading it from top to bottom like Chinese, but to no avail. Not least of all, I was befuddled by such an archaic and fussy word like, well… befuddled. Like an orphan stranded at the train station of avant-gardism, its glaring antiquated presence appears to be a cry for help. This is not to say that nonsense poetry hasn’t had a place in literature, we have Edward Lear and Edith Sitwell. However, Lear and Sitwell relied on the euphonic quality of the words and adhered to a strict sense of meter and rhyme. In short, there was some sense of aesthetic – something remarkably lacking in Ms. Marlis’s exercise.

How would one recite one of these? The only recourse I could think of was to bark out the fragments in the deranged manner of a homeless man who is encountering a delusional episode. And the listener? (Or reader?) Well, what on earth would make you think the listener should have anything to do with the crafting of a poem? As the poet and critic Joan Houlihan remarked in her essay “Post-Post Dementia” that these poems are driven less by a need to communicate than a need to afflict.

“Like the almost-dead in the film ‘28 Days Later’ these poems are poised to bite any reader who ventures too close, hoping to infect them with the same virulent strain of avant-gardism inflicted on them by their maker who has doomed them to a life of aimless, disembodied wandering through people-less landscapes. Who has loosed these babbling and afflicted beings into our public byways, and why? Who are their makers?”

You have seen their makers if you have attended a poetry function (I hesitate to use the word “reading” here) in the past decade: their navels proudly displayed and duly pierced; festooned with colorful tattoos that would turn a Pictish chieftain green (or should I say, blue) with envy, chattering away in that curious gurgling argot born of MFA programs and post-post feminism. These are, after all, people who can actually mouth the words “ongoing hegemonic appropriations” with a straight face. And it should come as no surprise that in her brief bio, Ms. Marlis tells us she has named her dog “Sappho”.

Imaging one of these denizens of the underground (or their spawned poems) leaping out and biting you with a virulent strain of anything does not take nearly the leap of imagination you might suspect.

How did poetry become so, well, so damned ugly?