The Road to Wigan Pier

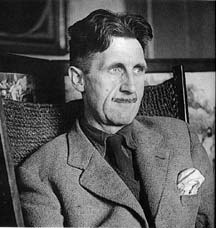

George Orwell 1903 - 1950

When I was seventeen, I found a paperback copy of George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier at a yard sale. The acid paper of the cheap Signet edition had browned with age and was crumbly to the touch. The drab, gray cover gave the retail price of thirty-five cents, inside the sale price of ten cents was written. No name, no inscription was to found on the inside of the cover; a brief description of the contents was printed on the back above a catalogue list of other inexpensive Signet editions.

What exactly a copy of this book was doing at a yard sale in western Indiana, I couldn’t say. I’ve speculated about it numerous times since; perhaps its subject matter - the conditions of coalminers in Northern England in the 1930’s - struck a familiar note with some of the locals as it was a coal mining region also, or its lengthy argument for joining the Socialist movement for Indiana was the home of the great American socialist, Eugene V. Debs might explain its presence, but there is no real way of knowing why the book was there.

If it seems I am inferring precociousness on my part, I would like to disabuse you of that now. I was only vaguely aware of the coal mining industry and its history in my corner of the world. Of course, the slag heaps, and the occasional tunnel collapse brought it to the dimmest reaches of my consciousness, but I had no sense of its history or the effect it had on my home.

As for the socialist aspect, it was certainly quite fashionable in 1970 to describe oneself a socialist, or a radical of some kind; but again, it was hardly a well thought out political or philosophical stance. Suffice it to say the authority figures in my life - teachers, coaches, priests, and policemen - were all unified in the view that socialism was a bad thing: therefore, it deserved my unswerving attention.

It was as a result of one of my many infractions with the aforementioned authorities that I came to read The Road to Wigan Pier. I had been sentenced to several days confinement to a study carroll to think over what I had done. Truthfully, I have no recollection of my transgression, but in all probability it had something to do with some surly remark, or insolent rolling of the eyes that were correctly perceived as a sign of disrespect.

If I read the introduction, I have no memory of it. It was not until several years later while at the university did I understand the significance of Victor Gollancz disavowel of Orwell's peculiar take on what he had been commissioned to do. Gollancz had assigned Orwell to produce a documentary account of unemployment in the North of England for the Left Book Club. In part, Orwell succeeded, but it was nothing the orthodox leftists had expected and I will return to that in a moment.

But, there is one memory of that day seared into the very fiber of my being, and that was the following passage:

"The train bore me away, through the monstrous scenery of slag-heaps, chimneys, piled scrap-iron, foul canals, paths of cindery mud criss-crossed by the prints of clogs. This was March, but the weather had been horribly cold and everywhere there were mounds of blackened snow. As we moved slowly through the outskirts of the town we passed row after row of little grey slum houses running at right angles to the embankment. At the back of one of the houses a young woman was kneeling on the stones, poking a stick up the leaden waste-pipe which ran from the sink inside and which I suppose was blocked. I had time to see everything about her—her sacking apron, her clumsy clogs, her arms reddened by the cold. She looked up as the train passed, and I was almost near enough to catch her eye. She had a round pale face, the usual exhausted face of the slum girl who is twenty-five and looks forty, thanks to miscarriages and drudgery; and it wore, for the second in which I saw it, the most desolate, hopeless expression I have ever seen. It struck me then that we are mistaken when we say that ‘It isn’t the same for them as it would be for us,’ and that people bred in the slums can imagine nothing but the slums. For what I saw in her face was not the ignorant suffering of an animal. She knew well enough what was happening to her—understood as well as I did how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling there in the bitter cold, on the slimy stones of a slum backyard, poking a stick up a foul drain-pipe."

Although I did not find the subject matter of the book compelling at that time , it was the descriptive power of Orwell's writing that kept me riveted to the page. I had not read Orwell's more "popular" works at that time. His two biggest sellers, "Animal Farm" and "1984" were and, I suppose, still are the standard introduction to Orwell's oeuvre. But, it is in his journalism, where his real power lay, as in his essays such as "Shooting an Elephant", or his other two nonfiction books, "Down and Out in Paris and London," and "Homage to Catalonia".

Gollancz admits as much. What he was apologizing for was Orwell's rather blunt assessment of what the ordinary person thought of socialism in general. The following passages were just a few examples of what made the publisher of a rather orthodox leftist book club more than a little squeamish:

"In addition to this there is the horrible - the really disquieting - prevalence of cranks wherever Socialist are gathered together. One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words "Socialism" and "Communism" draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, "Nature Cure" quack, pacifist, and feminist in England."

"Sometimes I look at a Socialist - the intellectual, tract-writing type of Socialist, with his pullover, his fuzzy hair, and his Marxist quotation - and wonder what the devil his motive really is. It is often difficult to believe that it is a love of anybody, especially of the working class…"

"…And all that dreary tribe of high-minded women and sandal-wearers and bearded fruit-juice drinkers who come flocking towards the smell of "progress" like blue-bottles to a dead cat."

Keep in mind; this was Orwell's argument for socialism! At this point, his strong anti-communist stance was not as clear, that was to come later in his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, but what is clear is his perception and what he thought the majority of his fellow countrymen's perceptions of socialism were. Although he remained a socialist until the day he died, he hated, in that very English way, cant and orthodoxy excusing totalitarianism whether it came from the right or the left.

Timothy Garton Ash in his essay "Orwell in 1998" sums up for me why Orwell became the predominant figure in my development:

"In his best articles and letters, he gives us a gritty, personal example of how to engage as a writer in politics. He takes sides, but remains his own man. He will not put himself at the service of political parties exercising or pursuing power, since that means using half-truths, in a democracy, or whole lies in a dictatorship. He gets things wrong, but then corrects them. Sometimes he joins with others in volunteer brigades or boring committee work, to defend freedom. But if need be, he stands alone, against all the “smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls”."

2005 Barney F. McClelland

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home